Jan Estep, “The Southern Land Not Fully Known: Naming Antarctica,” Quodlibetica, Constellation 10: Cartographies, October 2010.

The Southern Land Not Fully Known: Naming Antarctica

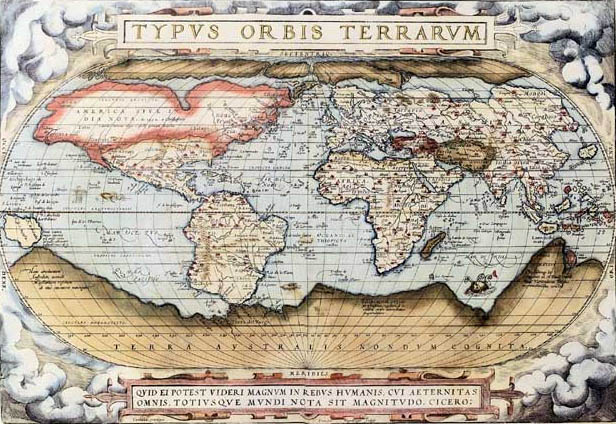

Abraham Ortelius, Ortelius World Map, 1570

In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries…

the Latin words “terra incognita” began appearing on European maps to mark unknown lands. The term had existed at least since the first century AD when the ancient Roman astronomer and mathematician Ptolemy postulated a southern continent of the same name. A Latin translation of Ptolemy’s Geography, a treatise on cartography, became widely available during the Renaissance, and the concept took hold. Some maps from this period represent terra incognita as undifferentiated blank space, neither land nor sea. There is a tolerance for emptiness and incompleteness that is rarely seen on maps today. Other illustrations were more speculative and populate these empty spaces with fantastic serpents and sea dragons, alluding to the dangerous ocean travel needed to discover it. Or the space is filled with long stretches of mountains, blocking access.

The Ortelius World Map, created by Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius in 1570, shows the uncharted territory below South America, Africa, and Asia as a solid, continuous landmass. Inspired by Ptolemy’s conjectures it was widely believed that the earth needed such a southern continent to balance the known continents to the north. As explorers pushed further south, looking for Terra Incognita and searching for new whaling grounds, they instead found passage around Cape Horn and discovered that this hypothesized landmass was not simply an extension of known areas. This landscape was far more differentiated than first surmised. But because of the hostile environment and relative isolation of the region, it took the next four centuries of exploratory shipping routes to cartographically delineate Antarctica, Australia, and the other island territories. A Russian expedition led by Fabian Gottlieb von Bellingshausen and Mikhail Lazarev first sighted Antarctica in 1820, and Norwegian Roald Amundsen and his team did not reach the South Pole until nearly a hundred years later in 1911.

Tracing the cartographic place-names for the southern polar region is a study in epistemological self-awareness. Gleaned from maps of the known world, each Latinate phrase communicates the degree of knowledge explorers had about the area. The place-names proceed from terra incognita (the land unknown), demarking a realm of total obscurity, to terra australis incognita (the southern land unknown), terra australis nondum cognita (the southern land not fully known), terra australis recenter invento sed nondum plene cognita (the southern land recently discovered but not yet fully known), and finally Antarctica, which made its first appearance as a continental name on maps created by Scottish cartographer John George Bartholomew in the 1890s.

The evolution of place-names reveals the historical conceptualization of the continent in both geographic and cognitive terms. At each moment the names articulate the current state of discovery and show how strongly our understanding is also a part of what is being labeled. The initial change from “land unknown” to “southern land unknown” separates the southern polar landmass from all the other terrae incognitae. The second shift from “unknown” to “not fully known” admits the relative meagerness of our knowledge: we know it, but not fully, a self-conscious indication that more answers and detail are needed. The third step from “not fully known” to “recently discovered but not yet full known” further underscores the progress in this direction: the “recently discovered” boasts of accomplishment and simultaneously qualifies the newness and thus tenuousness of the knowledge claims, while the “not yet” implies a “but soon to be.” The words emphasize the ambition to search until the continent is more thoroughly explored and “full knowledge” attained.

The Antarctic naming sequence also reflects a notable level of abstraction from pure geographic data. It points to the fact that maps are metaphorical as much as they are functional. Empirically maps can get us to a specific place and inform us about that place in a fairly reliable way; for this we treat them as objective, factual documents. Yet at the same time maps are essentially abstract representations, each an edited interpretation reflecting the cartographer’s subjective bias and focus. The cartographic impulse links the imaginative thinker with the real-world, on-the-ground explorer, charting the mind at the same time it maps the environment.

Antarctica’s place-names remind us of this duality by literally articulating the knower’s state of understanding. Reading these early maps, one cannot help but consider the act of knowing, which for most of Antarctica’s history is self-consciously partial and incomplete, young, and unfinished. Fittingly, the capstone name Antarctica, meaning “the opposite of the north,” suggests that our knowledge of this place will always be relative, never absolute. Collectively the names suggest that there is always more to learn, and always more to know, with great optimism that we are up for the task of further exploration.

copyright Jan Estep 2010